There are times when I am going through a newspaper, and I’ll come across an interview of someone, and it will be pitched as ‘edited extracts.’ Or the intro will say that the reporter and the subject spoke for four hours, and this is an condensed version. And it will be 800 words. And I will be gritting my teeth and saying, ‘Where is the full thing? Why not put out the full thing?’

Maybe the physical newspaper allows for only 800 words. But the internet has no restrictions. For those who’d like more, why waste the hard work of the interviewer and the subject?

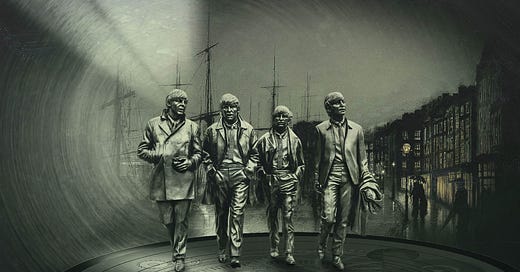

I felt a similar way while watching Get Back, the brilliant documentary series by Peter Jackson that uses old footage to reconstruct the recording of the Beatles album, Let it Be. Jackson had access to archival footage that amounted to 60 hours of video and 150 hours of audio. For someone like me, who’s been a Beatles fan for over 40 years, this is heaven. But we got just a few hours of it.

In this interview, Jackson speaks about his process of curating this footage. His first cut was 18 hours, and the task Disney gave him was to cut it down to two-and-a-half. He eventually brought it down to six, but didn’t want to cut more. “At that point,” he said, “you’re starting to commit a crime against rock and roll history if you start trimming more, because there’s stuff there that people have to see. They haven’t seen it in 50 years. Anything that we weren’t going to put in this film, I was painfully aware, is likely to go back into the vault for another 50 years.”

That last bit is italicized by me, and you can see why it is a horrifying thought. Luckily, Disney listened, especially after Paul and Ringo agreed with Jackson. But over here, a thought strikes me: why not put it all online?

The timeline I would choose as Disney is this: First, put the current version online. And then, at a later date, put Jackson’s 18-hour version online. And then, put the entire archival material online — all 60 hours of video and 150 hours of audio. (This would be subject to the Beatles agreeing, of course.)

Would Disney get more eyeballs from users? You effing bet they would. Engagement would be off the charts. You could even open-source the footage and let other film-makers have a go at it. (With due credit to those who created the original footage and those who restored it, of course.) Jackson was the right person to make the film if only one person could be chosen to make it — but that restriction doesn’t have to exist for a project like this.

Rethink Form. Everything you know is outdated

All conventional forms arose because of physical restrictions. I often speak on The Seen and the Unseen about how creators have to think beyond the restrictive formats at 30 years ago. A writer would think in terms of 800-word articles or 100k-word books etc. An episode for a TV series would be 24 minutes (the commercials would take it to 30), a Hollywood film around 90 minutes, a Bollywood film around 3 hours. You get the picture.

But the restrictions that led to those forms evolving no longer exist. I’ll elaborate upon this in my next post on the creator economy, but let me zoom in to one aspect of it for now: music.

I’ll often find people lamenting the death of ‘the album’ in this new age, but the album itself was such a restrictive form. The length of the album evolved because of physical limitations of how much music could fit on an LP Record. The convention for how long a song should be also arose out of similar constraints, which is why the three-minute-song became a radio convention. But there is no reason today for a song to have either an upper or lower limit, or for a band to release just a certain number of minutes of music at a go, and no more.

As you’d expect, creators everywhere have been ahead of the curve, but their mainstream gatekeepers have not. These gatekeepers will either die or get with it.

The other tragedy, it struck me while watching Get Back, is that there are many songs the Beatles performed that have never been released at all. This was due to the physical restrictions of format, as I mentioned above. Had the Beatles been active today, they’d have released everything. This would have been so incredible, right?

My favourite Pearl Jam recordings are all bootleg recordings from concerts. And the band has been wise enough to encourage the release of every bootleg recording out there. I see this becoming the norm. The bands I love, I love — warts and all. I don’t necessarily want the most slickly produced version of them. I want it all.

And Now Think Journalism

Aaron Sorkin just blasted a New Yorker profile of Jeremy Strong, saying that the writer Michael Schulman created “a distorted picture of Jeremy,” in which Sorkin himself appeared to be a participant. Sorkin was asked five questions about Strong, gave five answers, but “only one and a half of these answers were used,” cherry-picked to support Schulman’s narrative.

I won’t comment on this allegation or that specific story, but I will say that many profiles done in India fit this pattern. The writer will decide on the narrative in advance, and chase only evidence that fits that narrative. Often, the hit job that results will only have anonymous sources. If there is an ideological angle to this, then your entire echo chamber will celebrate. You might even win awards.

I was asked by a publication a couple of years ago to give background info for profiles they were writing on a couple of people. I spoke to the two reporters in good faith, but quickly realised that they’d decided on doing a hit job, and anything nuanced that I said was pointless. I kept a recording of those conversations, even though they were not on the record, to make sure my words weren’t twisted.

Those profiles didn’t appear, but this kind of thing does happen. What can be done to empower readers here? If I was the editor of a publication doing such pieces, here’s what I would do: in addition to the published piece, I would do a bonus dump of all on-the-record quotes, as well as a list of everyone the journalist tried to reach out to for on-the-record quotes. In the case of the New Yorker story above, that bonus dump would contain all five Sorkin answers.

This would allow readers to judge for themselves if the reporter had cherry-picked quotes. It would also enable them to detect intent and bias by seeing who the reporter approached for quotes on the story. Obviously, all stories have (and should have) a slant, and you always choose one narrative over others. But why not be transparent about this?

Note that you’d put nothing in this data dump that could not have been in the story. So nothing that was off the record, nothing that endangers anonymous sources. Nor am I saying that anyone should be mandated to do this. As an editor or a reporter, I’d do it voluntarily — I think it would enance my credibility, and create the right incentives for good journalism.

Also, it would empower readers. That’s what the internet allows us to do. It makes us less reliant on gatekeepers, and readers and creators benefit. But more on that in my next post.

Please subscribe, btw. It’s free!