So I’m sitting here in my neighbourhood Starbucks, trying to push myself to get some work done, when a thought strikes me. Or rather, a thought experiment strikes me.

Imagine a neta walks into Starbucks and goes to the counter. He demands coffee. There is a 10-minute exchange in which the friendly Starbucks person behind the counter, whose name is Preeti, takes him through all the options available. It is finally decided that our neta will have a grande cappucino.

Our neta is then told the price.

He takes off his Gandhi cap. He looks at it in amazement, though he is amazed at something else, not the cap. He wipes his forehead with it. He puts it back on. He blinks a couple of times. Then he looks into Preeti’s eyes and says:

‘You are an enemy of the people.’

‘Sorry, sir? What?’

‘You are anti-national. You are a greedy capitalist. You’re the exploitative class. You are sucking the blood of the people.’

At this moment, Preeti thinks, Can vegetarians suck blood? This is a rather irrational thought, but reason has left the building, so please forgive her.

‘Coffee at the Mantralaya costs 10 rupees,’ says our Neta. ‘This is a poor country. Even 10 rupees would be too much. And you are charging… this?’

‘Sir, if you take a Starbucks membership, you will get points for your purchase.’ Preeti hears the words coming out of her mouth with horror.

The neta hasn’t heard her, though. He is in his own flow.

‘Coffee is a basic human right,’ he says. ‘Everyone should be able to afford coffee in a democracy. Coffee brings us meaning. Coffee brings us dignity.’

Preeti, by now, is having an out-of-body experience. She looks on from the ceiling as this girl who looks just like her says: ‘Sir, can I offer you an Almond Cookie along with that? It has been democratically elected as the finest cookie in South Asia.’

Our Neta grunts, turns around and attempts to walk out of the Starbucks, crashing into the pristine glass door instead.

*

A week later, the government comes out with an order that reads thus:

The government hereby announces price controls on all coffee sold in the city of Maharashtra. The maximum price for a cup of coffee will now be Rs 10. This will be applicable to the largest size available in a cafe. Free espresso shots must be available for pedestrians who enter and ask for them. Coffee is a basic human right. Also, almond cookies are hereby banned. Government inspectors may enter at any point and taste all cookies to make sure there is no trace of almond.

So here’s the thought experiment: what will happen if such an order is passed? I am not being flippant: take a minute off and think about the consequences.

The Hidden Life of Humans

I want to change the subject for a moment by talking about one of the great books of this century: The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben.

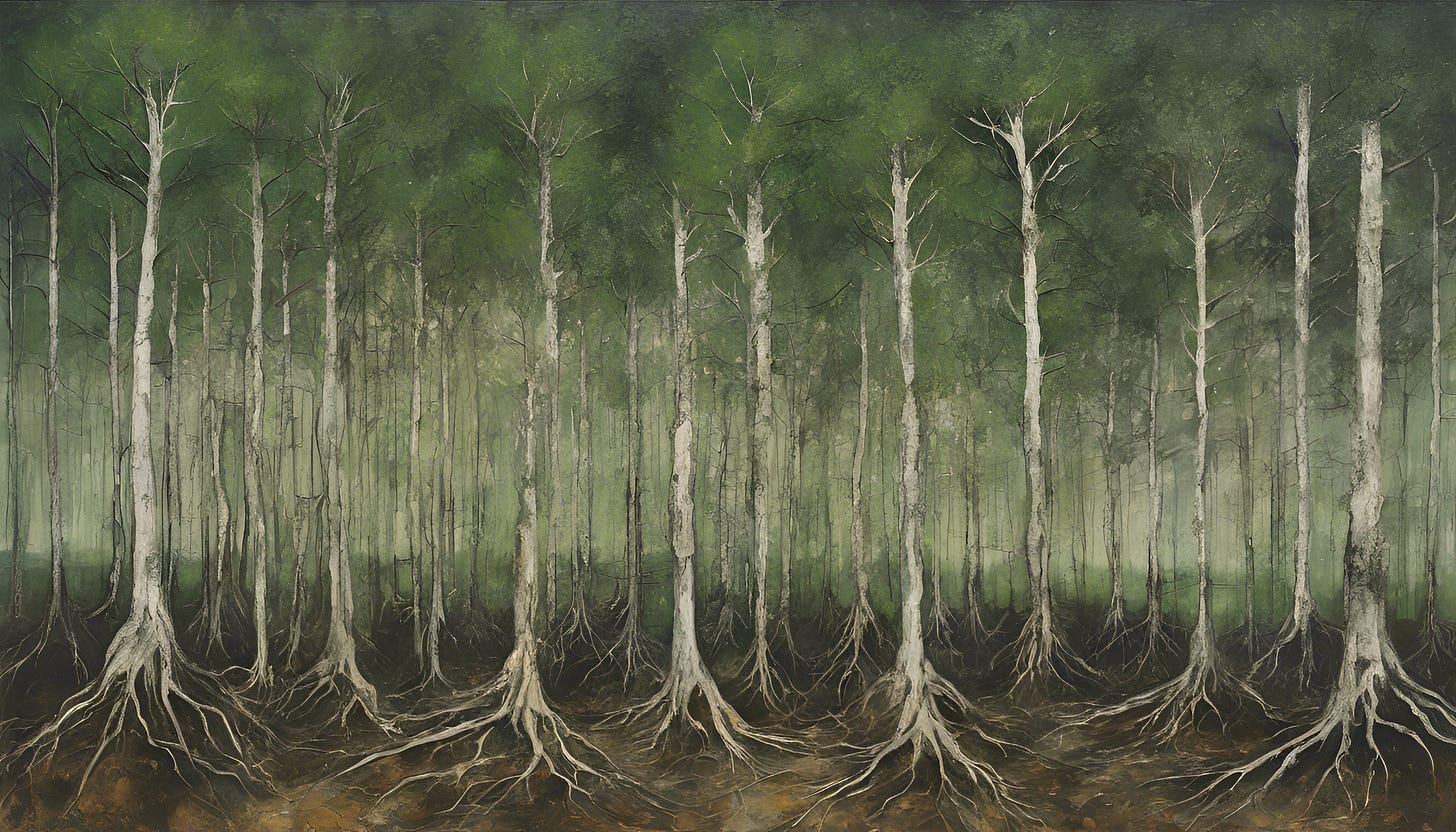

One of the things I learned from this great book is that trees are not stately solitary creatures, as we often think of them, but social beings. In fact, they’re a classic illustration of The Seen and the Unseen. What is Seen is that they are standing alone above the ground. What is Unseen is that they are connected under the ground by networks of roots, using fungi known as mycorrhizal networks to pass on information to each other.

This article by Richard Grant is a good primer on the subject. He quotes Wohlleben thus:

All the trees here, and in every forest that is not too damaged, are connected to each other through underground fungal networks. Trees share water and nutrients through the networks, and also use them to communicate. They send distress signals about drought and disease, for example, or insect attacks, and other trees alter their behavior when they receive these messages.

Reading Wohlleben’s book will fill you with a sense of awe. He calls these networks the ‘Wood-Wide Web.’ What a beautiful world we live in.

And how do humans communicate? Once again, let me bring in The Seen and the Unseen. What is Seen — and heard, of course — is that we speak to each other, and write to each other, and communicate through language. But for many things, this doesn’t scale enough, and the limitations of language kick in.

How a society communicates with itself, how each of us can have a finger on the desires and capacities of all of us, is through prices.

The great Frédéric Bastiat once asked, ‘How Does Paris Get Fed?’ A central planner would not be able to feed Paris on his own. To understand the preferences of each individual, to do the procurement of the food that is required, to coordinate with farmers and suppliers, is simply impossible. But all of this happens every day anyway, as if by magic.

Prices make it happen.

Prices are signals. Prices are incentives. Prices enable us fulfil the desires of others who we don’t know, and who don’t know us, for our own benefit. Prices are magic.

The moment when I realised this was a turning point in how I think about the world. Everything changed. If what I am saying sounds odd to you, please spend a few minutes reading what I consider to be the most important essay of the 20th century: Friedrich Hayek’s masterpiece, The Use of Knowledge in Society.

And also Leonard Read’s I Pencil.

Wake up and Smell… Hey, Where’s the Coffee?

It’s easy to see what happens in the thought experiment I mentioned earlier in this essay. Everyone who can’t make coffee profitably for less than Rs 10 stops making it. Starbucks, Blue Tokai and Third Wave Coffee shut down. Even Udupi restaurants take coffee off their menu.

Meanwhile, a black market springs up for good coffee. A flat white can cost more than 1000 bucks, as the vendor has to factor in the risk of being outside the law. Only the underworld makes coffee now. And there is a government program called The War on Coffee.

This is not an absurd thought experiment. This shit happens, if not with coffee so far.

For example, just yesterday, I came across this news of how the Karnataka government has imposed price controls on all taxis in Banglore, including Uber and Ola. No more surge pricing! The government will make sure that taxis are affordable for all!

This will backfire, and hurt exactly those people it is supposed to help.

If prices are not allowed to function freely, there will be a disruption is society. What will happen to the information they carried? What will happen to the incentives they carried?

A few years ago, I wrote a piece on for The Times of India called ‘Price Controls Lead to Shortages and Harm the Poor.’ To save myself effort — I am Bengali and don’t like to work — let me quote from there:

How do prices work? Why do price caps hurt? I like to illustrate this with the example of Uber’s surge pricing. This mimics markets, with prices responding in real time to supply and demand. It has also caused much outrage, with users often complaining about Uber’s exploitative pricing during peak hours. Perfect example.

Imagine a miniature Uber world in which, at a specific moment, there are 50 available cars for 100 customers. There’s a mismatch between supply and demand, and Econ 101 tells you that the price should go up. But Dear Leader puts a price cap. What will happen?

Two things. One, the 50 available cars go to customers on a first-come-first serve basis, and 50 customers are left stranded. Some of those who are left stranded may have urgent needs, like catching a flight or going to hospital in an emergency. They would value the ride more. They would be willing to pay more. Some of those who do get cars may have a trivial need, and would gladly not take the trip if the price was too high. (They could use public transport or Netflix-and-chill at home.) First-come-first-serve doesn’t distinguish between the two. A surge price would reflect the scarcity of the ride, and signal its true value.

There is a second effect that is deeper than this allocation effect. A high price sends a signal to the marketplace. It incentivises Uber drivers taking a break to make themselves available. More cars get on the road. More needs get served. Over the long term, the money in driving Ubers might even incentivise people to move from less profitable professions to driving taxis. In a free market, prices carry the information that push people towards deriving the best value from their skills. Price caps stop this information. They perpetuate imbalances between supply and demand, which the market would otherwise sort out.

Whenever a ban on Uber’s surge pricing has been tried out in India, it has led to shortages. A friend of mine actually missed a flight in Delhi when the government there experimented with it. What if she had a medical emergency at that time?

I am off to Bangalore in the second half of this month to record a bunch of episodes. Luckily, the hotel where I stay is across the road from the studio where I record, and next to the best book store in the world, so I won’t need an Uber. But if you live in Bangalore, do watch for how the policy affects cab availability. I predict scarcities.

This is not rocket science, btw, but Econ 101. Price controls always lead to scarcities. Here’s an old prediction I got right.

What is the Price of This Essay?

In monetary terms, this essay is free. That said, even though I didn’t charge for it, you paid. Time is money, and you got to the end. Thank you for valuing my thoughts.

This is not a paid newsletter, and will not be one anytime soon. So all I ask from you is that you share it with anyone who might be interested — and if you haven’t already, please subscribe. More importantly, share these thoughts, if not the piece itself. They matter.

You and I, we are also part of a mycorrhizal network. Let’s keep reveling in this forest of ideas.

***

Illlustrations by Simahina.

***

Lovely post overall. But on a related idea of how stories can take on lives of their own, see here for example on the wood-wide web theories (or at least it’s grander claims as made in pop sci): https://undark.org/2023/05/25/where-the-wood-wide-web-narrative-went-wrong/. And more narrowly, the perils of most pop science books/articles in exaggerating claims and often misrepresenting research findings.