Trapped Inside the Infinite Scroll

How we engage with the world makes us who we are

Earlier today, I recorded my sixth episode of The Seen and the Unseen with Ramachandra Guha. The joy of recording the kind of conversations I do is that I end up reading so many great books for them. The one that is fresh in my head right now is Ram’s latest, The Cooking of Books: A Literary Memoir. This is a both “a memoir of friendship” and “an elegy to a lost world,” among the phrases Ram offers up in his preface for how to look at this book. You could say it is the life and times not of a person, but of a friendship.

At the other end of this friendship is the reclusive Rukun Advani, who edited many of Ram’s books, and indeed set him on his journey towards becoming the historian he is. I won’t write about the book here, though, but an aspect of it: the letters the two men wrote to each other.

The book is full of excerpts from those letters, and they are a joy. They are thoughful and thought-provoking and unfiltered and intimate, and reveal both men to be such fine thinkers. (I’ve reproduced an excerpt I loved at the end of this post.) This got me to thinking about something I first explored with Chandrahas Choudhury in a Seen/Unseen episode long ago: what does it mean for us that we no longer write long letters with pen and paper, but instead send emails and texts?

I am probably in the last generation of actual letter-writers. I remember writing long letters in the 1990s — to my mother, after I moved away from home for the first time; to random friends I am not in touch with any more; to the girlfriend I later married. The act of gathering the sheets of lined paper, or the inland letter card, and sitting down with a physical pen indicated that this person is important to me. Why else would I make such an effort?

To write with pen and paper is to write without a backspace. And because each letter has to be a certain minimum length to justify the effort, there is a lot to say. I would mull over what I would say in a letter before I got down to writing it. My words would be considered — and because I was often writing about myself, they would force me to turn my gaze inwards. Thehrav was forced upon me by the form.

At one level, we continued writing letters, only in an electronic medium. But it wasn’t the same. Form changes content. Most of my emails are terse and instrumental. Ok, see you at 7 today. That kind of thing. I never bare my soul to anyone. I never self-reflect.

Does this change not just the manner of our communications, but also the nature of our friendships? Does this change the kind of person we are?

I think often about how the texture of our days — the things we do all day — is so different today. I released a Seen-Unseen episode today with Ira Pande, and in the intro I mused:

How do we engage with the world? In modern times, we can reach out and touch many more parts of the world than we once could. Or so it seems: all the knowledge humans have gathered is a click or a swipe away: every film ever made, every song ever recorded, every book ever written – it’s all there at our fingertips, with an ocean of new content created every day. And yet, while our breadth of exposure to the world has increased, our depth has reduced. We are always clicking, swiping, alt-tabbing, trapped in the illusion of movement that the infinite scroll gives us. I am not complaining about others here: my own engagement with the world has become choppy. I jump from sliver of experience to sliver of experience. And I can remember another life, in another century, when I wasn’t like this. I could immerse myself in something – and often didn’t have a choice, because there wasn’t so much that was fighting for my attention. I’m not making an argument for the good old days – I’m happy I get to see these times, and to benefit from them. The problem is not in having more choices open to us, but in fixing the way in which we interact with them.

The thing is, no one stops us from writing long letters. Indeed, Ram and Rukun still write each other long letters in their email — Ram showed me a delightful example of that on his phone. But they were writing like that to each other long before the internet, and they continued that habit. Some of us haven’t.

No one stops us from doing deep work and from ignoring our smartphones. It is up to us to take control of our lives, and to accept only the good things that technology can give us. But I accept that we are frail and flawed, and this is hard.

Are You a Simmering Six?

I came across a tweet by George Mack yesterday that began with the following statement:

Semi-controversial opinion: There’s no such thing as working too hard. There’s just being under rested.

You should read the full post for yourself, but I’ll try to summarise it. Mack’s point is that working too hard is not a problem — not getting enough rest is. It is okay to work for 16 hours in a day — as long as you get the sleep you need in the other eight hours. (To understand the importance of sleep, I recommend you read Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker. If you haven’t read it, you need to read it.)

If you think of working at 10 as full intensity, and working at 0 as complete rest, then we should make sure we get enough 0 in our life — that will enables the 10s. But, too often, we are in a perpetually stressed and distacted state in which there is no 0, and so there is no 10. Mack quotes Josh Waitzkin:

Most people in high-stress, decision-making industries are always operating at this kind of simmering six, as opposed to the undulation between just deep relaxation and being at a 10. Being at a 10 is millions of times better than being at a 6. It’s just in a different universe.

Mack gives examples of how going to 0 for a while can help you bounce up to 10. Here’s one:

Eleanor Roosevelt credited one thing to surviving her White House schedule for 12 years: Before meeting crowds or giving a speech, she would sit still, close her eyes and relax for 20 minutes.

In an earlier post, I mentioned a ritual we have developed for Everything is Everything: once the cameras are rolling, the four of us — Ajay, Nomsita, Vaishnav and I — sit silently for five minutes with our eyes closed. We go down to zero — and I find that this helps us focus much better in the hour of shooting that follows.

I was telling this to Pranay Kotasthane just now at the Takshashila office, and he said that these days, when a webinar starts, he and his students will begin with a minute of silent mindfulness. I love this!

We need to find ways to force the noise of the world to stop. I am a work in progress. What about you?

Community and Isolation

In another tweet I discovered yesterday, Gerard Dawson wrote:

Algorithms are the anti-village.

He said this is a different context, but I find it thought-provoking on its own. Traditionalists in India will often lament, and modernizers will celebrate, the journey we made from joint families to nuclear families. I often point to how we have gone beyond this, from nuclear families to atomized families.

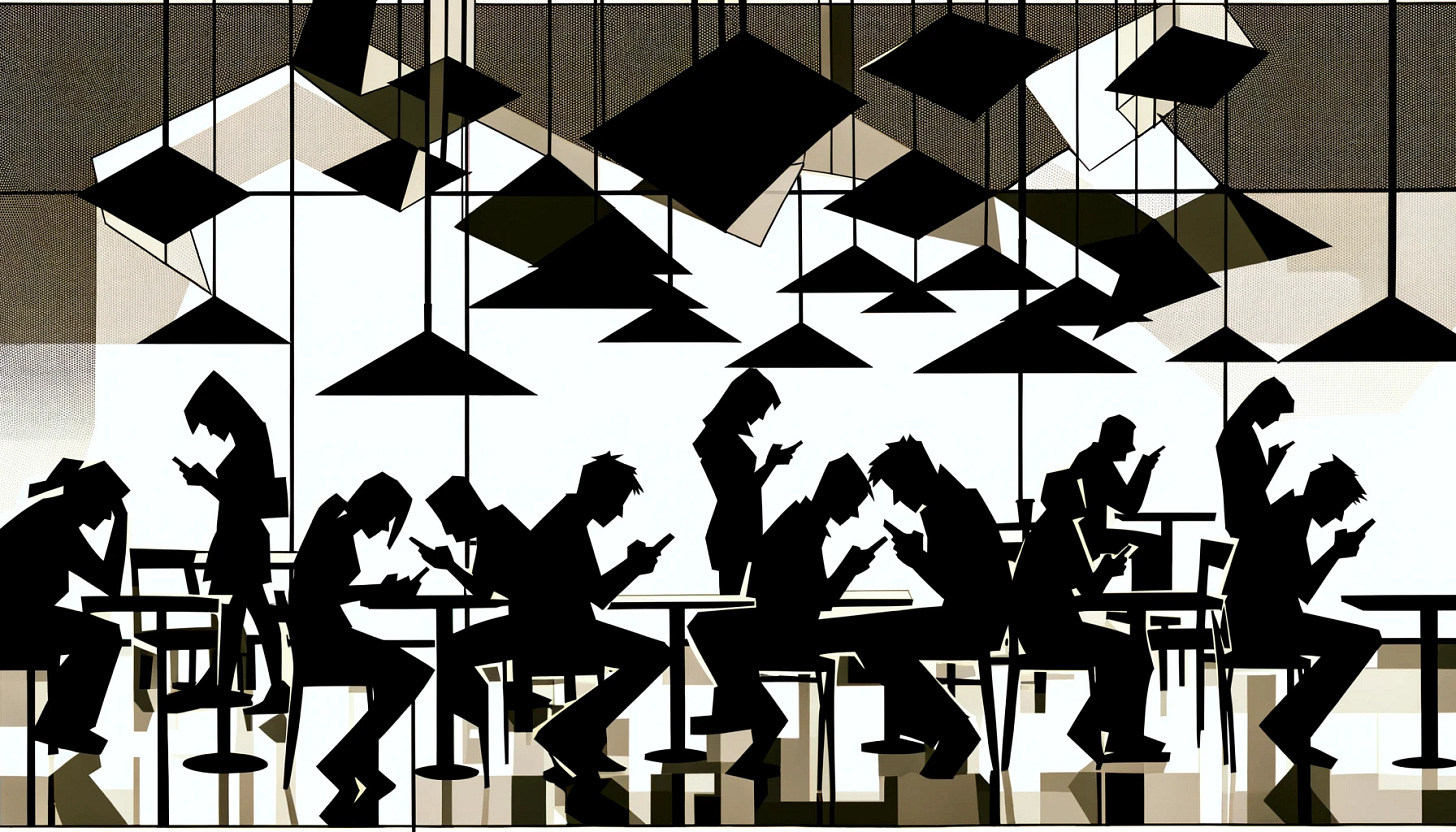

If the classic image of the nuclear family is a Mommy, Daddy and two kids sitting down at a dining table, my image for the atomized family is Mommy, Daddy and two kids sitting down at the dining tables staring into their phones.

Hell yes, our smartphones can be instruments of individual empowerment. But they can also strip away any sense of community we might otherwise develop. They may seem to connect us to the world — but they can also disconnect us from it.

You may even be reading these words on your phone right now. Isn’t it ironic, don’t you think?

‘Emotions Recollected as Hype’

And now, as promised, here’s an excerpt from The Cooking of Books. It’s from a letter Rukun Advani wrote to Ram Guha about an event two decades before this was written. This is a letter mind you, not a published and celebrated essay.

I like your descriptions of Clive Lloyd and Viv Richards. I too was at the Kotla, watching Viv hit all those sixes against Bedi & Co during his 190 or so. Exhilarating experience. I thought the central difference, really, between Lloyd & Richards was that Richards’ stylish savagery was communicated by his face and body language – everything about him spoke when he was being lethal; but with Lloyd, on the other hand, there was a hugely attractive gorilla-like languor, a cordial and impassive ease about that brutal belting he was dishing out, as though hitting a four was a form of politeness, like sipping tea. He seemed so inoffensive and so casually benign even as he whiplashed all those balls flat to the ropes. To me he communicated a philosophical rectitude on a job well done, something impersonal he was impartially executing rather than anything personal against any particular bowler or team. That made him seem different and even more exalted than Viv Richards, in a way – because most of the power batsmen (e.g. Tendulkar) are more in the Richards than the Lloyd mould in the sense that they are so personally involved in their art and communicate that involvement through face and body. Lloyd seemed a kind of lama among batsmen. Plus of course he looked like a battle-tank in the path of even the fiercest ball approaching his region and you got the feeling he’d let nothing through, as much because he didn’t want to, as because he was just impartially there, placed there by God on a cricket field to stop balls. I’m sure I have a rather romanticized recollection of Lloyd, but then what else is cricket-watching except emotions recollected as hype?

I guess one takeaway I can end with is that you should write more letters.

And if not more letters… more newsletters?

***

A plug, since I mentioned Pranay and Takshashila: Applications for their celebrated PGP course are open now. Sign up!

***

Illlustrations by Simahina.

***

'A good work ethic needs a good rest ethic' is the mantra I used in my 35+ year career - and it served me well.

Rukun's Lloyd vs Ricrads excerpt et al was pure magic - thanks for sharing. I heard Ram at the BIC sometime ago - I look forward to listening to your TSTU episode with him.

Mathew Walker's book is unfortunately a lot of hype with bad data. While we need to sleep, after you read his book, you will come away believing that every illness in the body is related to poor sleep. His book is considered a form of "churnalism" - to be taken with a big pinch of salt.

Agree with everything else you said. The more rested you are, the better is your productivity.