The year before Covid, my father sat me down in the living room of his house in Chandigarh. ‘Tell me about your childhood,’ he said. ‘I don’t remember anything.’

He was in the throes of dementia then, aware of it, struggling to come to terms with both mortality and what was left of life, reading Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal. I had heard that when memory fades for those with dementia, the edges remain sharp. They remember their childhood, they remember yesterday, but what is in between begins to fade. Just like that, the best years of your life vanish.

This seemed to be the case with him. During that trip, I sat with him with a digital recorder and asked him questions about his life. They were vivid all the way up to adulthood, though he was too shy, even in his late 70s, to say much about his love affair with my mom, which was reportedly a scandal in 1960s Calcutta. There was no doubt that his memories of her were sharp; his memories of me, less so.

I didn’t give a clear answer to his question that day. Most of what I remembered of my childhood did not have him in the frame. Some of what I remembered of him was pleasant; but some was not. There was no point talking about that to a man who no longer felt the anger he once had. I don’t think he would have remembered why he was angry for so much of his life; or even that he was angry to begin with. I don’t even know how I know — I think I saw it in retrospect.

He died in Covid’s second wave, and a few months later, I went to clear out the house we had sold. I found a community library in Delhi to donate most of the books to, and decided to chuck everything else. (I spoke about it in this episode.) All I would keep is signs of who my parents were as people: letters and diaries that would help me get a sense of their interior lives. I found some remnants, but nothing substantial.

They lived in an age before technology enabled the large-scale storage of memories. They did not take a selfie on their wedding day; there are no home videos of me as a kid; Facebook has no memories of them to throw up. I do have this old video of my mother performing her music, but I don’t know what to feel when I see it. I also have some camera-phone videos of her from 2008, when she was dying of pancreatic cancer. In one of them, she looks at the camera and sweetly says ‘Bye!’ She wasn’t bidding goodbye to either me or life at that moment, and the moment was humorous, so I don’t remember the context. I don’t feel anything when I watch it — it is a random moment that just happened to get captured. But I find it hard to think of more memorable moments — in my head, I see a spasmodic montage, and it is difficult to slow down and zoom in.

My father’s memory deteriorated to the point that shortly before he died, he seemed to have lost his sense of personhood. I don’t know if he knew what was happening to him at the end. I don’t know if that is a blessing or a curse.

It did raise the question in my head though: what is a person if not an accumulation of memories? And when those memories fade, what is left? Are we then a bundle of animal instincts again?

Memory = Storytelling?

While researching for my Seen/Unseen episode with Aanchal Malhotra a few years ago, I discovered an aspect of memory I hadn’t known. The first time we remember an event, we are remembering what happened. But every time after that, we remember the last remembering of it. And each time, details can change and the memory can shift, like in a game of Chinese Whispers.

Think of all the times you’ve been chatting with someone close about a shared memory — and you realise that both of you remember it completely differently. It can feel bizarre; but it doesn’t mean that one of you is lying. You just remember it differently, and because memory is nebulous, none of our rememberings need to be a wilful lie.

I’ll think aloud here and speculate that our memories may be a useful storytelling tool. How do we navigate a complex world which we are not equipped to understand fully? We do it by forming simple stories about it that help us feel we have a grip on things. These stories don’t have to be true; they just have to be useful.

With our memories, we construct a story of ourselves and our own lives. This is not the primary purpose of memory; but it is an important effect. And without realising it, we do our remembering in accordance with the story we are telling ourselves about ourselves.

The two most popular episodes of The Seen and the Unseen are The Loneliness of the Indian Woman and The Loneliness of the Indian Man. In the second of those, Nikhil Taneja told me about how he was once teaching a class of young people, and he asked each person to tell them a story of who they were. The first story was banal; but the second one was moving, the floodgates opened, and everyone began to share. If you listen to that part of the episode without tearing up, you are either not human or you failed the emotions-walla Turing Test.

Many of us do not even think about the story we tell others about us; and the story we tell ourselves. Making it explicit, making remembering an act of intention, is an interesting project. It may not make you happier, though. Self-reflection is hard because we’re all fucked-up.

Can You Shape Yourself Through Writing?

I came across this tweet recently by a professor named Ben Myers in which he talks about how his 94-year-old grandmother has kept a list of every book she has read in the last 80 years. He gives a picture of a page from the list, and it’s beautiful. His grandmother also wrote a memoir, and a later thread has diaries with poems and quotes that she noted down — but just the list itself is a memoir of sorts. Whatever you write down about yourself is a story of your life.

In the first of my Seen/Unseen episodes with Amitava Kumar, we spoke about the power of journaling. Since then, I keep asking my writing students to start a journal. It can be private, I tell them; it need not be more than a couple of hundred words a day; if they have nothing to write about, they can just write about the mundane events of that day — but write!

Writing helps you understand the world better, because you are forced to think about it. Writing helps you understand yourself better. And as understanding can shape our selves, writing helps you shape yourself.

Here’s a thought experiment. The world splits into two parallel universes right now. In one, you journal every day for five years. In the other, you do no writing for five years. How will the two Yous be different?

The answer is obvious to me. One of your future selves will have a deeper understanding of themselves and the world. That You will be smarter and more sorted.

Now you choose who you want to be.

Are You Happy Now?

Here’s something that I have wondered aloud about on the podcast: when you remember being happy at a particular point in time, were you actually happy then, or are you happy now in the remembering of it? Or are you superimposing happiness on your past self because it fits your story? What is happiness anyway?

I remembered this when Piyush Tank responded to a tweet of mine about Daniel Kahneman by posting a Kahneman video he likes. It’s from a conversation he had with Lex Fridman, in which Kahneman says:

I abandoned happiness research because I couldn't solve the problem. I couldn't see. [It is] very clear that if you do talk in terms of those two selves, then that what makes the Remembering Self happy and what makes the Experiencing Self happy are different things. And I asked the question: “Suppose you are planning a vacation and you're just told that at the end of the vacation you'll get an amnesic drug, so you remember nothing and they'll also destroy all your photos. So it'll be nothing. Would you still go to the same vacation?”

It turns out we go to vacations in large part to construct memories — not to have experiences, but to construct memories. And it turns out that the vacation that you would want for yourself if you knew you would not remember is probably not the same vacation that you will want for yourself if you will remember.

Kahneman has a great TED Talk about the Experiencing Self and the Remembering Self, so check that out. And now, before I end this post so that I can fondly remember ending it, I want to say two contradictory thoughts out loud for you.

One, we should focus on being in the moment as much as possible, being the Experiencing Self, and not spoil the way a sunset makes us feel by taking a picture of it. Be a person, not a story.

Two, we should deepen our sense of self by being intentional about remembering. We should write every day, and reflect on ourselves.

Both of these are possible. We contain multitudes.

And now let me end with a song that I loved as a teenager, which is a strange time to love a song like this, isn’t it?

***

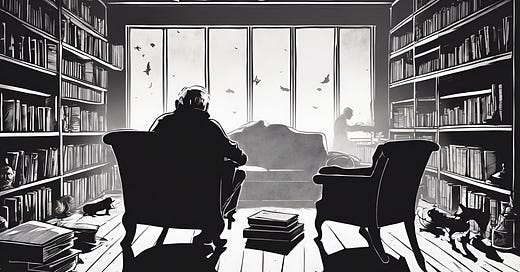

Illlustrations by Simahina.

***

Read Being Mortal recently. It's beautiful book. I am big fan of your podcast, everything is everything and your occasional newsletter. Keep it up.

Memories of past keep us alive today. At this age (I am in my late 60s) memories are precious especially our childhood memories. Now is miss digging out more from my parents about their childhood. Lesson for future generations...keep asking till it's too late

I have my father's notebooks, recording every book he had read in his post-working years. Maybe inspired by that, or becoming aware of my own deteriorating memory, I too have been keeping a record these last few years.

My father also had a notebook full of poems/snippets of poems that he had copied.....